Blogs

Djedefre Pyramid

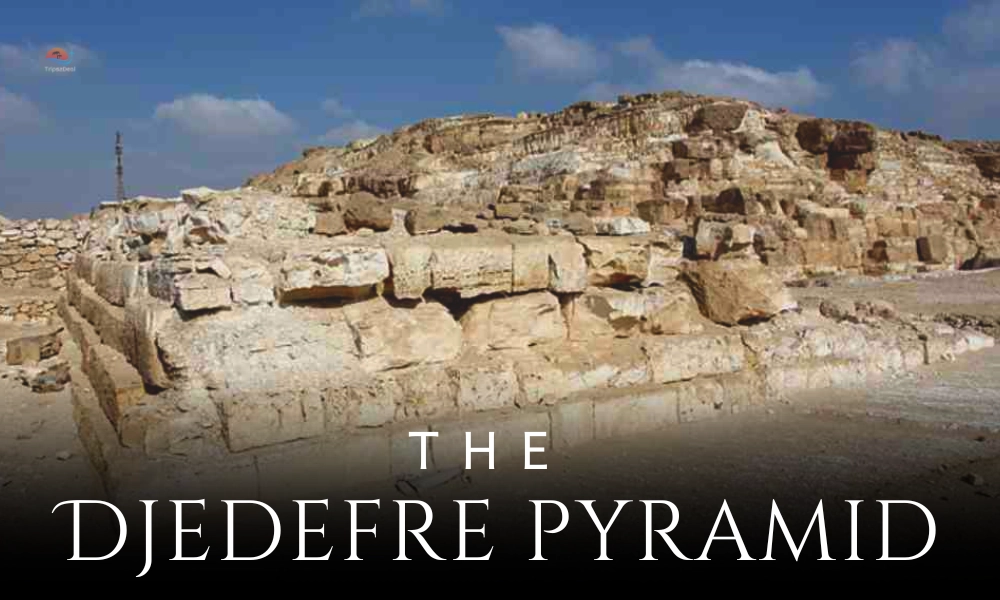

A few miles northwest of Giza, on the high and windy hill of Abu Rawash, may be seen the remains of one of the most curious royal residences of the Old Kingdom. It is a complex of pyramids for Djedef (Radjedef), the son and heir. It belongs to the same UNESCO necropolis as Giza, Saqqara, and Dahshur. It became the final pyramid in Egypt, constructed to the north.

Table of Contents

Who was Djedefre?

Djedefre was a king at the beginning of the 4th Dynasty of Egypt, a successor of Khufu, and a predecessor of Khafre. Close is his connection with the cult of the rising sun; he was one of the earliest kings to use the epithet Son of Ra, and the nickname of Abu Rawash, opposite the holy city of Heliopolis, perhaps foreshadowed the cult of the sun.

Setting and scale

The location of Abu Rawash is about 8 km (5 mi) west of the pyramids of Giza. It rests on a high plain, which provides a lookout of the Nile Valley. The site has been commonly quarried since the early Roman and early Christian ages, and it is because of this that only low courses of the superstructure and the cut bedrock core are now visible.

Although in a ruinous condition, measurements taken by scientific workers have shown that there was a large monument: its base approximately 106.2 m on each side and a rough original height in the 57 to 67 m range with a slope of about 48 to 52 °, distinguishing it as one of the Menkaure class of pyramids.

Design and engineering

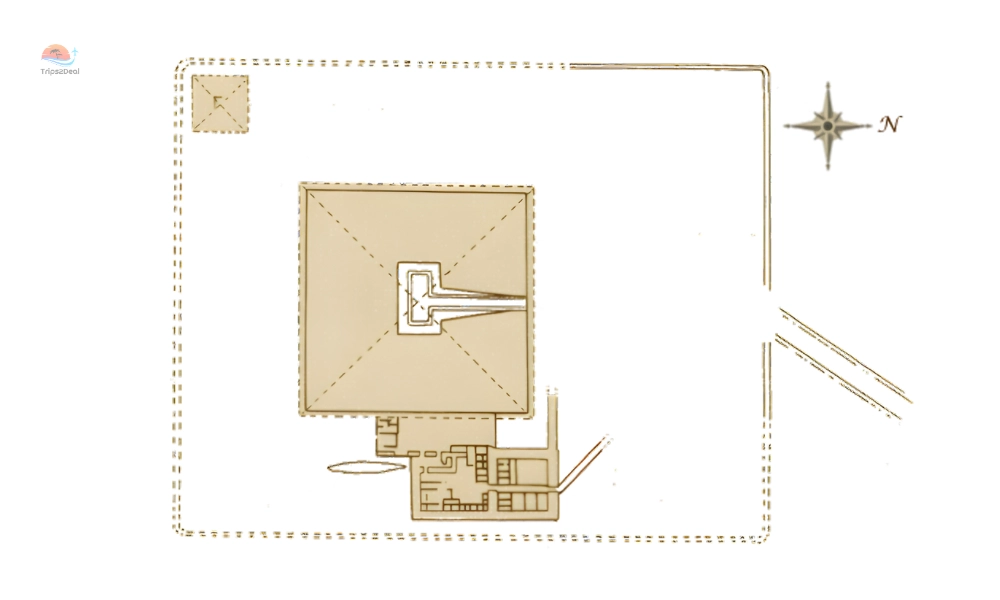

The builders of Djedefre used a natural hillock as a part of the core and drilled an enormous central hole about 23 x 10 m and approximately 20 m deep. This cut was approached by a sloping passage of 49 m., as was customary on the north side (which descended into the burial area), and this passage still is in keeping with the old technique of the step pyramids, though it is of the true pyramid epoch.

The pyramid complex

To the south or east, a large boat pit was discovered by excavators. It has no timbers yet, but the shape is interesting, and more importantly, the contents are part of over a hundred red-quartzite royal statues with painted heads of Djedefre. One of the heads, now located in the Louvre, is frequently cited as one of the first known images of a royal sphinx.

As with other royal complexes, the Djedefre had:

- An east side mortuary temple (now preserved largely in mudbrick and rubble).

- There is a southwestern satellite pyramid.

- An approach (traces remain) that had connected to a lost valley temple was found.

Was it finished?

Over the decades, the destruction at Abu Rawash led many to believe that the pyramid of Djedefre was incomplete. French teams have argued later (and a detailed report published in 2011) to the contrary that the building was at least substantially developed, perhaps finished, and that subsequent excavation explains its mutilated state. The dialectic is not fully resolved, yet the view of 'completed, then destroyed' is now well established in the academic field.

Finds and meaning

The fragments of the statues out of red quartzite and the sphinxes indicate an active royal cult here, though much of the finished stone may have been removed.

The elevated location, sun worship, and hybridity of the structure (a deep, Saqqara-style deep-well pit fused with a Giza-era true pyramid) of the monument of Djedefre are a transition point between the era of experimentation and the canon of the pyramids.

Visiting the site today

Below, you can find the rugged bones of a royal project, the stepped courses of the foundation, the dramatic trench to the central pit, the fragments of temples scattered about, and jaw-dropping vistas to the Giza Plateau.

This is precisely what makes Abu Rawash intriguing: its bare condition gives us an idea of the engineering behind the casing. It provides a rare, behind-the-scenes view of how these monuments were fixed to bedrock and space.

Why the Djedefre Pyramid matters

Even in its destruction, the Abu Rawash complex transforms our image of kingship in the 4th Dynasty. It depicts a ruler bending towards the sun-god Ra, testing the ground with composition, while remaining in the pyramid tradition and establishing a cult that left a heavy legacy of statuary. However, later centuries may reuse the material. Although still under construction, the lost pyramid of Djedefre continues to reveal Egyptian views of eternity, landscape, and royal leadership.

Conclusion

The pyramid of Djedefre at Abu Rawash appears ruined now; people removed the stones of the former, though it was a serious project of the king on a high ridge. It depicts a king associated with the sun deity Ra, intelligent cutting into rock, and indications of a comprehensive temple complex. Even in fragments, it serves to show how the early 4th Dynasty shifted between experiment and the classic Giza style.